By Carol Stiffler

While you were sleeping Monday night, Shelly Franklin was wide awake. With an eye toward the night sky and the aid of a handful of at least 10 celestial apps on her phone, Franklin was waiting for the northern lights to appear.

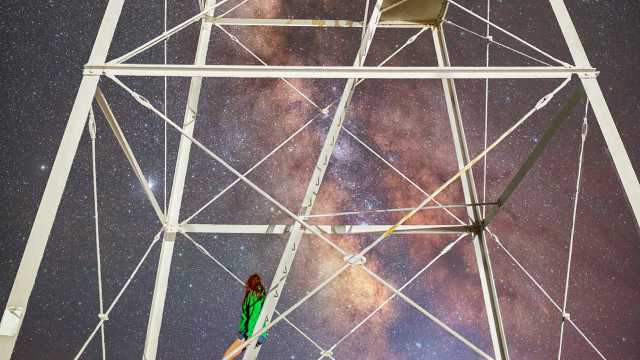

She’s the rarely seen face behind the Michigan Milkyway photography business. Her Facebook page, listed under Michigan Milkyway, has more than 29,000 followers. You’ve probably seen her shared images; they tend to go viral.

From her home in Lakefield, Franklin is quite used to leaving in the dead of night to capture images that are often mindblowing. The Mackinac Bridge under the stunning Milky Way. Miner’s Falls floating dreamily next to a rainbow of northern lights. A comet streaking over the Tahquamenon Falls.

Franklin is a self-taught photographer who’s always been interested in the night sky.

“I was pretty determined that I was going to see what was going on up there,” she said.

She does it with costly equipment and a telescope mount that moves to compensate for Earth’s rotation. That’s how she manages to take pictures with the lens of her camera open for sometimes 13 minutes at a time, letting in more light from outer space than the unaided human eye can detect.

Franklin has turned the hobby into a sustaining business, and she’s been at it for enough years that she’s developed excellent night vision.

“Using a flashlight actually ruins your night vision for about 20 minutes,” she said. “When I’m out at night, for as much as I can, I minimize using any kind of light.” That kind of “exercise”, as she calls it, lets her see more than a huge white cloud when she studies the Milky Way – the galaxy that Earth calls home.

She describes herself as a loner and says she likes to be alone. She travels with companions as often as she can, but is also willing to spend hours outside alone at night. She brings bear spray, too.

That’s been fine most of the time, but Franklin recalled one photo session on Long Point when a large animal silently came very close to her. Normally very attentive, Franklin said she was distracted by mosquitoes and had her hood up, which narrowed her line of vision. When her camera flashed at the end of its long exposure, the animal startled and ran away with such force that it shook the bridge she was standing on. She presumes it was a bobcat or cougar, but didn’t get to see it.

She doesn’t usually get scared at night, but on that evening, she packed up and left immediately.

“That’s the only time I left somewhere,” she said. “I’m not giving this thing another chance.”

To stay comfortable when she’s out alone at night, Franklin talks to herself – loudly. “It’s entertaining,” she said. “ I don’t really get freaked out. I used to. But it’s almost exposure therapy: The more you go out at night, and nothing happens to you, you realize you are okay.”

Franklin is more than okay. She essentially makes a living off her photos, which she prints and sells. She also accepts contract work – she’s shooting a middle-of-the-night wedding on Sugarloaf Mountain later this summer, and she is often hired for memorial work, like nighttime shots on a beach where a loved one’s ashes were distributed. Each year she accepts one or two students and teaches them her line of work, and she is sometimes paid to speak at night sky presentations.

“Being outside at night, under a clear sky – that is a good sky – is probably the only time my mind is quiet,” she said.

Franklin encourages people to try spending time outside at night – even without a camera.

“Get a clear night and go outside,” she said. “Get outside and look around. Clear your mind. It’s good for you.”

Photo credits: Shelly Franklin